I have written many tech tips about invasive species ranging from what they are to specific pests. Most of the time, these invasives fit into the classifications of insects and plants. Some can be extremely destructive while the hype on others is overblown.

The latest invasive, Lycorma delicatula—the spotted lanternfly (SLF)—is an insect that is on the move.

The detection of SLF goes back to September 2014, when these insects first made an appearance in eastern Pennsylvania. There were many hypotheses derived at that point with regard to food source, potential mobility and means of spread, some of which may not have been completely correct.

Of course, this is why it’s called a hypothesis. Over the past decade, many of the characteristics have been identified while some aspects are still being researched. What has become apparent is that they are on the move.

What is SLF and Where is It?

The spotted lanternfly is an invasive insect native to Asia, likely brought to the U.S. accidentally through international importation.

It doesn’t have natural predators in North America. Its red coloration is a sign to most predators that it tastes bad, and they stay away. SLF is a plant hopper type of insect. Nymphs cannot fly. Adults have wings; however, they are not great flyers. Instead, they climb to higher points of a tree or structure, jump off and glide from there. This initially gave researchers the sense that they would not spread quickly, but they have found a way.

What has been determined is that adult females like to lay their eggs on smooth surfaces and often that ends up being rusty metal. When that surface happens to be on something mobile, for instance a train car, over-the-road truck or other vehicle, the eggs are then easily transported to other areas to start a new outbreak.

What has been determined is that adult females like to lay their eggs on smooth surfaces and often that ends up being rusty metal. When that surface happens to be on something mobile, for instance a train car, over-the-road truck or other vehicle, the eggs are then easily transported to other areas to start a new outbreak.

To date, SLF populations are confirmed in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Delaware, New York, Ohio, Michigan, Indiana and North Carolina, so the spread is evident and more rapid than initially anticipated.

Most recently in terms of detection, there was a nymph identified in central Iowa. The old saying likely holds true—where there is one, there are probably more. Long-term prediction of the spread has the insect making its way through most of the central portion of the country in a pattern as far south as central Texas and north through Canada. Several areas of California and the Pacific Northwest are predicted to be heavily affected as well.

What is the Threat?

SLF originally were thought to feed almost completely on another invasive species—Tree of Heaven, Ailanthus altissima. This scenario wouldn’t pose much of a risk as these trees are more of a nuisance and are not commonly used in the landscape.

Upon further investigation, it has been determined that the insect will feed on more than 70 species of plants, including many maple, pine and willow species along with several others. The preferred hosts seem to be maples, particularly silver, and black walnut for ornamental trees, but most fruit trees including grapes and hops may be at the greatest risk.

SLF has piercing-sucking mouthparts to suck plant juices. Like other insects that feed the same way, they filter out the nutrients that they can best use, then secrete the remainder of that fluid as waste called honeydew.

When populations are high, this can add up to copious amounts of honeydew which leads to sooty mold. This will be a problem for outdoor living areas and landscapes alike. Honeydew is also an attractant for ants and stinging insects looking for a sugary meal. Secondly, the insect feeds through all life stages, making this a problem throughout the year.

What Should I Know?

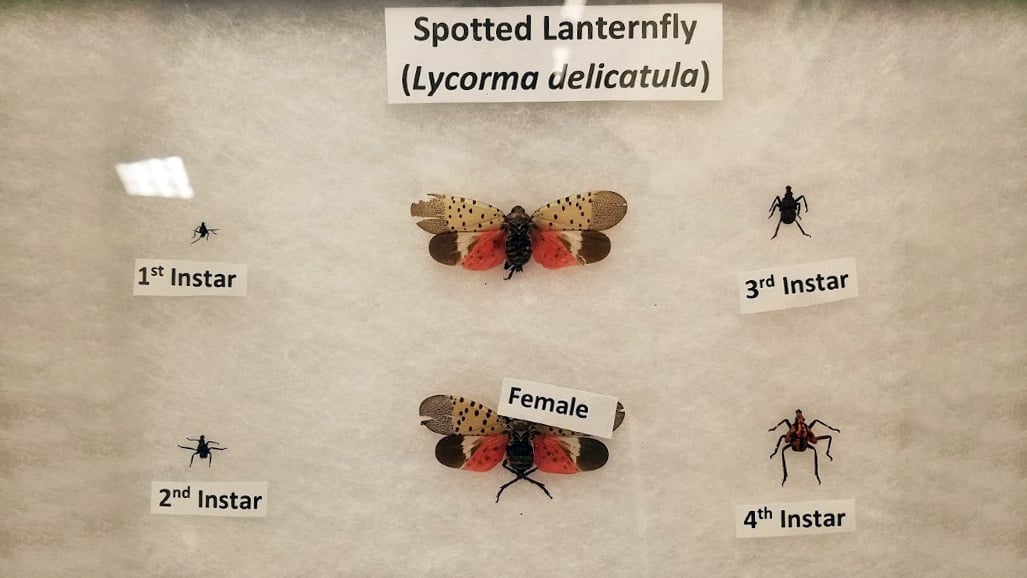

It appears that there is only one generation per year, making the act of scouting somewhat more straight forward. Nymphs hatch in the spring then will go through four nymphal stages called instars. During each of the first three stages, they appear as black, crawling insects with white dots. In the fourth instar, they are red with white dots.

Nymphs will give rise to adults which will begin to appear as early as midsummer and will persist until late fall/early winter. During this time, females will lay egg masses with between 30 and 50 eggs per mass. Each female can lay egg masses twice. These egg masses can look like a muddy smudge, which can easily be passed over when inspecting for hitchhikers. Egg masses can be scraped and smashed, but should also be reported.

What is the Latest?

A recently released update is specific to the risk of healthy trees, revealing that healthy trees seldom succumb to the feeding of SLF alone. Heavy feeding can lead to weakened trees that can be finished off by secondary invaders or environmental and other stresses. This is not consistent with the potential damage to grapes and hops, where heavy feeding has caused significant damage in grape vines and crop production.

What Can Be Done?

Many chemical manufacturers have filed for 2(ee) labeling on insecticides showing good efficacy on SLF populations.

This gives an applicator the ability to use a control product in a manner that is not specifically labeled, or in other words, a special circumstances label. The contact insecticide Bifenthrin I/T and Talstar P both have 2(ee) labeling along with Imidacloprid T&O 2F. Formulations of dinotefuran namely Zylam liquid and Safari 20SG received 24(c) labeling which is an additional use label for SLF in 15 states, including New York. More states will be added as the need arises.

Lean on Us for Pest Control Solutions

Feel free to contact myself or Pat Gross, Ewing’s Tech Team, with your turfgrass questions. Email me at klewis@ewingos.com or call/text 480-669-8791. Email Pat at pgross@ewingos.com or call/text 714-321-6101.